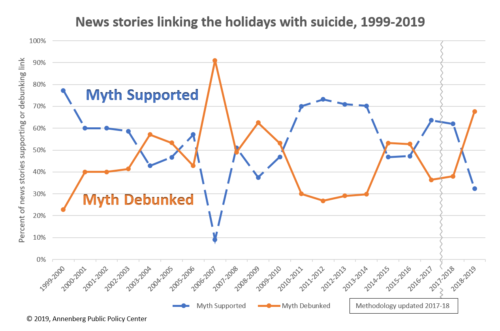

A greater proportion of news stories in the last holiday season debunked the false connection between the holidays and suicide than supported it, the strongest showing in over a decade of coverage of the holiday-suicide myth, according to an analysis by the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania.

In the 2018-19 holiday season starting before Thanksgiving and lasting through January 2019, over two-thirds of the newspaper news and feature stories that mentioned the holidays and their connection to suicide debunked the myth that suicides rise over the holidays, a reversal of the coverage the prior year.

“We were fortunate in having a number of press stories that effectively debunked the myth,” said Dan Romer, research director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC). “We’re hopeful that the message is getting out: While this time of year may be emotionally fraught for some people, there’s no truth to the idea that the suicide rate peaks over the holidays.”

The 2018-19 analysis showed that of the 34 articles mentioning the holidays and a rise in suicide, 68% debunked the holiday-suicide myth and 32% supported it – the highest debunking rate since the 2006-07 season. The current analysis is based on stories in the Nexis or NewsBank databases and excluded stories with coincidental references to suicide and a holiday. (See Figure 1.)

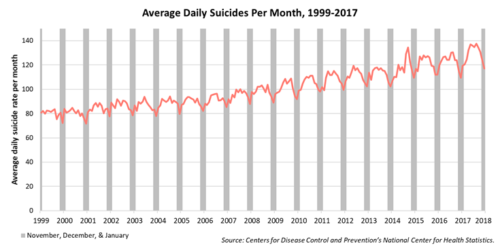

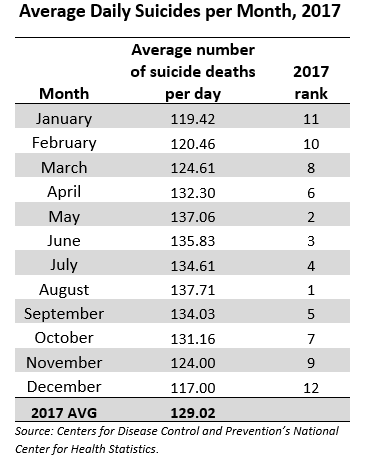

The holiday season typically has some of the lowest monthly suicide rates, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC data from 2017, the latest full year available, show that the month of December had the lowest average daily suicide rate, ranking 12th, followed by January (11th), February (10th) and November (9th). In 2017, the months with the highest average daily suicide rates were August and May. (See Figure 2 and Table 1.)

The debunking message breaks through

APPC has analyzed news coverage of the holiday-suicide myth for 20 years, since the 1999-2000 holiday season. In most of those years, more newspapers have upheld the myth than debunked it. In only three of those years, including this past season, did more than 60 percent of the news stories tracked debunk the myth.

This past year most stories — including some which cited APPC’s efforts to make the public aware of the CDC data — debunked the connection:

- A letter to the editor of the Galveston County (Texas) Daily News takes issue with an article published earlier in December, pointing out that “According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suicide rates are at their lowest in December, contrary to the referenced article.” (Dec. 28, 2018)

- An article in the Taunton (Mass.) Daily Gazette on suicide prevention notes that the CDC has said the suicide rate is lowest in December. (Dec. 31, 2018)

- The Charles City (Iowa) Press wrote: “Several recent studies have debunked the long-held belief that suicide rates rise sharply during the holidays, however the fact remains that Christmastime can be difficult to handle for individuals who have some mental illnesses.” (Dec. 23, 2018)

In addition, two stories this past year – in the Philadelphia Inquirer and USA Today – were widely republished by other news outlets, which is not reflected in the story count. The USA Today story included possible reasons that suicides tend to rise in warmer weather while the Inquirer article, “The media’s holiday suicide myth will never die,” looked at the persistence of the myth and noted that “November and December perennially have the lowest rates of daily suicides, CDC data show.” (Dec. 13, 2018)

Perpetuating the holiday-suicide myth

Despite the evidence, in the 2018-19 holiday season some publications continued to support the false connection between the holiday season and suicide:

- An editorial in the Eastern Arizona Courier observed that the number of suicides in the local area were down, but added: “It should be noted we’re now in the holiday season, when suicide attempts increase; still, we remain optimistic.” (Nov. 26, 2018)

- A well-meaning letter to the editor published in the Kansas City (Mo.) Star said: “The holidays can be a difficult time for people. Every year, the suicide rate increases during this season.” (Dec. 4, 2018)

- A columnist for the Grayson County (Ky.) News Gazette wrote, “For some people Christmas is not a welcomed time and not one for celebration. Crimes, murders and violence rise during Christmas. Suicides increase and psychiatric treatments go up.” (Dec. 15, 2018)

- The Jacksonville Journal-Courier (Ill.) quoted a county coroner as saying suicides “are usually geared more toward the holiday season, so you always brace yourself for that.” (Jan. 9, 2019)

It should be noted that the methodology for identifying news stories changed this year. We expanded our search by also including stories from the NewsBank database, which has greater coverage of the U.S. press than Nexis alone. Using this expanded coverage in a reanalysis of the prior year did not change the proportion of stories identified in 2017-18 that supported the myth.

Not only did the proportion of stories debunking the holiday-suicide myth increase in the last holiday season, but the number of stories supporting the myth decreased from 31 in 2017-18 to 11 in 2018-19.

Why the correct information is important

Romer said that giving people the sense that suicide is more likely during the holidays can have adverse consequences. For vulnerable individuals who are contemplating suicide, such news can have contagious effects, which is why the national recommendations for news-media reporting about suicide advise journalists not to promote information that can increase contagion, such as reports of epidemics or seasonal increases, especially when the claim has no basis in fact.

Journalists helping to dispel the holiday-suicide myth can provide resources for readers who are in or know of someone who is in a potential crisis. Among those offering valuable information are the CDC (http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/suicide/holiday.html), the Suicide Prevention Resource Center (www.sprc.org) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/suicide-prevention). The U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 800-273-TALK (8255). The Federal Communications Commission recently approved a plan to create a three-digit phone number for suicide prevention, 988, but it is not yet in operation.

The Annenberg Public Policy Center worked with journalism and suicide-prevention groups that produced recommendations (http://www.reportingonsuicide.org) to guide reporters writing about suicide. The recommendations say that reporters should consult reliable sources on suicide rates, such as those produced by the CDC, and provide information about resources that can be helpful to people in need.

Methodology on holiday-suicide myth stories

News and feature stories linking suicide with the holidays were identified through the Nexis and the NewsBank databases. The search used the terms “suicide” and (holiday or Christmas or New Year) and (increase or peak or rise) from November 15, 2018, through January 31, 2019. The search methodology changed this year with the inclusion of the NewsBank database alongside Nexis. In addition, this year the analysis included the terms “increase” or “peak” or “rise.”

Researchers determined whether the stories supported the link, debunked it, or showed a coincidental link. Only domestic suicides were counted; overseas suicide bombings, for example, were excluded. Thanks go to Ilana Weitz and Lauren Hawkins, who collected and supervised the coding of the stories and to Sebastián Lemus Camacho and Alba Disla for assistance in coding. Sharon Black of the Annenberg School of Communication provided technical support. Thanks also go to Alex Crosby and his colleagues at the CDC for providing monthly rates of suicide in the United States.

Download this news release here.