Preface

Disinformation, hate speech, and extremist propaganda are not new. Over the past decade, however, massive use of commercial technology platforms and search engines has created a fertile environment for such venom to spread virally, and citizens and policy makers on both sides of the Atlantic are seeking new ways to mitigate harmful impacts.

Nations in both Europe and North America enjoy a strong tradition of protecting freedom of expression, based on common democratic values. But rather than conducting insular Europe-only and U.S.-only debates, we need a transatlantic, values-based discussion.

Thus, the Transatlantic High Level Working Group on Content Moderation Online and Freedom of Expression was convened by the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania. The Transatlantic Working Group (TWG) includes a wide spectrum of voices, drawn equally from Europe and North America, with 28 prominent experts from legislatures, government, large- and medium-sized tech companies, civil society organizations, and academia.

The members were selected not as representatives of specific companies or organizations, but rather for their ability to tackle tough policy issues coupled with a willingness to work with those of differing viewpoints to find a path forward that would be well-grounded in legal, business, and technology realities.

By collaborating across the Atlantic, we sought to bolster the resilience of democracy without eroding freedom of expression, which is a fundamental right and a foundation for democratic governance. We searched for the most effective ways to tackle hate speech, violent extremism, and viral deception while respecting free speech and the rule of law.

Through a freedom-of-expression lens, we analyzed a host of company practices and specific laws and policy proposals, gathering best practices from these deep dives to provide thoughtful contributions to regulatory framework discussions underway in Europe and North America. During the year, following each of three group sessions, we published three sets of working papers—14 in total, plus three co-chairs reports—all available online.1 After a quick but essential review of approaches to freedom of expression on both sides of the Atlantic, our first two sets of papers assessed selected regulatory and industry efforts to address hate speech, terrorist content, disinformation, and intermediary liability. The third set built on the prior two sessions, focusing on artificial intelligence, transparency and accountability, and dispute resolution mechanisms.

Over the three multiday sessions during a yearlong journey together, the views of many members evolved as we set our course during a rocky period for tech/government relations in Europe and North America. Conducting our sessions under the Chatham House Rule fostered trust that facilitated candid and productive debate.

We did not seek unanimity on every conclusion or recommendation, recognizing that diverse perspectives could not always be reconciled. This final report of the Transatlantic Working Group reflects views expressed during our discussions and charts a path forward.

Our partners

The TWG is a project of the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) of the University of Pennsylvania in partnership with The Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands and the Institute for Information Law (IViR) of the University of Amsterdam. The TWG also received generous support from the Kingdom of the Netherlands Embassy in the United States and the Rockefeller Foundation Center at Bellagio, Italy.

And our thanks

The co-chairs are deeply grateful to our final report drafting team, led by Peter Pomerantsev and Heidi Tworek; to the members and steering committee of the TWG for their dedication and policy contributions; and to our senior advisor and chief researcher, all of whom are listed in Appendix B. We also are indebted to our former European co-chair, Nico van Eijk, who stepped down to chair the Netherlands Review Committee on the Intelligence and Security Services. Our colleagues at the Annenberg Public Policy Center, led by director Kathleen Hall Jamieson, were extraordinary partners, problem solvers, and facilitators, to whom we owe much. Finally, we thank our many experts and advisors whose research and counsel were invaluable.

Susan Ness

Co-Chair

Marietje Schaake

Co-chair

The Transatlantic Working Group

Leadership

- Susan Ness, Distinguished Fellow, Annenberg Public Policy Center; Former Member, Federal Communications Commission; Distinguished Fellow, German Marshall Fund

- Marietje Schaake, International Policy Director, Stanford Cyber Policy Center; President, CyberPeace Institute; Former Member of European Parliament (Netherlands)

- Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Director, Annenberg Public Policy Center; Professor of Communication, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania

Members

- Michael J. Abramowitz, President, Freedom House

- * Barbora Bukovská, Senior Director for Law and Policy, ARTICLE 19

- * Peter Chase, Senior Fellow, German Marshall Fund (Brussels)

- * Michael Chertoff, former Secretary, U.S. Department of Homeland Security

- Damian Collins, Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

- Harlem Désir, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media; former French Minister of State for Europe Affairs

- Eileen Donahoe, Executive Director, Stanford Global Digital Policy Incubator; former U.S. Ambassador, UN Human Rights Council

- Michal Feix, Senior Advisor to the Board of Directors and former CEO, Seznam.cz

- * Camille François, Chief Innovation Officer, Graphika

- John Frank, Vice President, United Nations Affairs, Microsoft

- * Brittan Heller, Counsel, Corporate Social Responsibility, Foley Hoag LLP

- Toomas Hendrik Ilves, former President of Estonia; Stanford Cyber Initiative Fellow

- Jeff Jarvis, Professor and Director, Tow-Knight Center for Entrepreneurial Journalism, City University of New York

- David Kaye, UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression

- Emma Llansó, Director, Free Expression Project, Center for Democracy and Technology

- Benoît Loutrel, former head of the French social network regulation task force; former Director General of ARCEP

- Katherine Maher, Executive Director, Wikimedia Foundation

- Erika Mann, former Member of European Parliament (Germany); Covington & Burling advisor

- * Peter Pomerantsev, Agora Institute, Johns Hopkins University, and London School of Economics

- Laura Rosenberger, Director, Alliance for Securing Democracy, German Marshall Fund

- Abigail Slater, former Special Assistant to the President for Tech, Telecom & Cyber Policy, White House National Economic Council

- Derek Slater, Global Director of Information Policy, Google

- * Heidi Tworek, Associate Professor, University of British Columbia

- * Joris van Hoboken, Professor of Law, Vrije Universiteit Brussels; Associate Professor, University of Amsterdam

(* Steering Committee)

Executive Summary

Five years ago, regulating social media was a niche discussion in most democracies. Now, there is a global discussion dealing with how, not whether, to regulate online platforms for communication. Lawmakers, journalists, civil society, and academics have criticized internet companies, and especially social media companies, for enabling the spread of disinformation, hate speech, election interference, cyber-bullying, disease, terrorism, extremism, polarization, and a litany of other ills. The scope of these potential harms is vast, ranging from political speech to content that may be harmful but not illegal to manifestly illegal content.

Many governments have passed laws or launched initiatives to react to these problems.2 Democratic governments have for a long time legitimately regulated illegal content. In many ways, this was easier before the internet, as print and broadcast media were often centralized entities that exercised editorial control. The online world, where a massive amount of speech is generated by users rather than their website hosts, presents additional new challenges, not only from the content, but also from its algorithmically directed reach. Current government initiatives, however well-meaning, sometimes use frameworks from the broadcast and print era to deal with user-generated content. This approach, while understandable, can risk curbing free speech even as governments strive to protect it.

The Transatlantic High Level Working Group on Content Moderation Online and Freedom of Expression was formed to identify and encourage adoption of scalable solutions to reduce hate speech, violent extremism, and viral deception online, while protecting freedom of expression and a vibrant global internet. The TWG comprises 28 political leaders, lawyers, academics, representatives of civil society organizations and tech companies, journalists and think tanks from Europe and North America. We reviewed current legislative initiatives to extract best practices, and make concrete and actionable recommendations. The final report reflects views expressed during our discussions and charts a path forward. We did not seek unanimity on every conclusion or recommendation, recognizing that diverse perspectives could not always be reconciled.

“How can we make sense of democratic values in a world of digital disinformation run amok? What does freedom of speech mean in an age of trolls, bots, and information war? Do we really have to sacrifice freedom to save democracy—or is there another way?”

The Transatlantic Working Group was motivated by our underlying belief in the importance of the right to freedom of expression and its corollary, the right of access to information. Freedom of expression is a fundamental right enshrined in international law, but it is more than that. It is a principle that enables all individuals to express their opinions and insight. It is above all the mechanism that holds governments and societies to account. This accountability function of the right to freedom of expression is the cornerstone of democratic societies, and distinguishes them from authoritarian forms of government. The recommendations thus incorporate freedom of expression principles from the outset, or the principle of freedom of expression by design. This includes safeguarding freedom of expression in any discussions around altering intermediary liability safe harbor regimes.

One key mechanism to address problems with online content moderation is to open up platform governance to greater transparency. Specific forms of transparency are a first step toward greater accountability and to repairing the lost trust between platforms, governments, and the public.

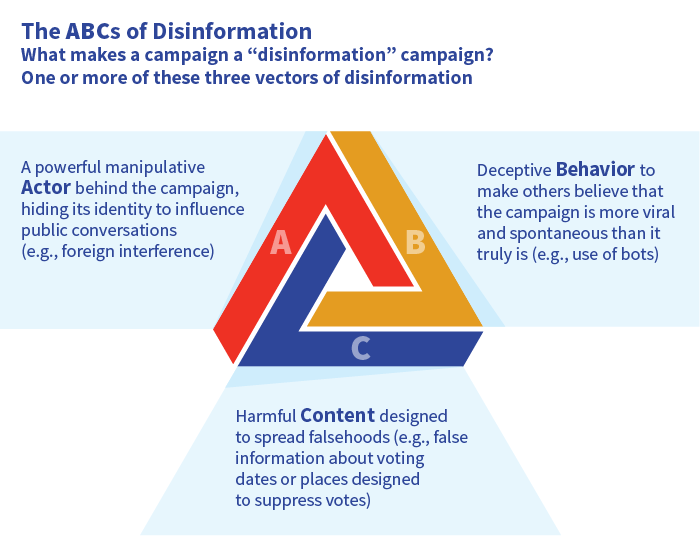

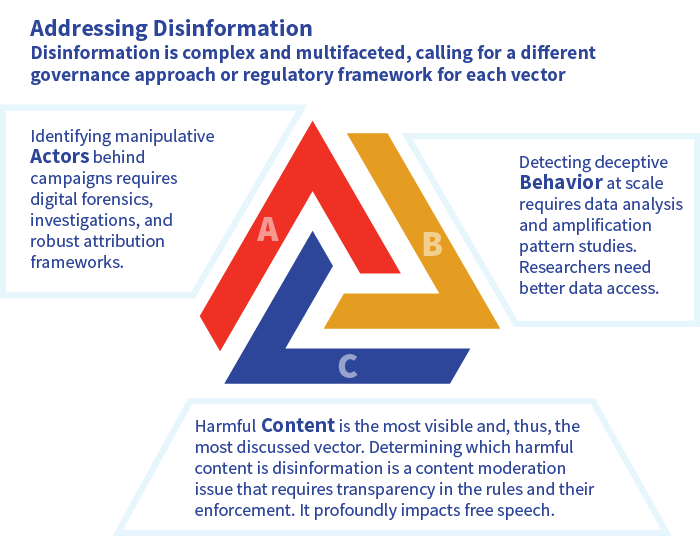

This report thus recommends a flexible regulatory framework that seeks to contribute to trust, transparency, and accountability. It is based upon: (1) transparency rules for platform activities, operations, and products; (2) an accountability regime holding platforms to their promises and transparency obligations; (3) a three-tier disclosure structure to enable the regulator, vetted researchers, and the public to judge performance; (4) independent redress mechanisms such as social media councils and e-courts to mitigate the impact of moderation on freedom of expression; and (5) an ABC framework for dealing with disinformation that addresses actors and behavior before content.

- Regulate on the basis of transparency: Transparency is not an end in itself, but a prerequisite to establish accountability, oversight, and a healthy working relationship between tech companies, government, and the public. Transparency has different purposes for different actors. Transparency enables governments to develop evidence-based policies for oversight of tech companies, pushes firms to examine problems that they would not otherwise address, and empowers citizens to better understand and respond to their information environment. Platforms have significant latitude to develop the rules for their communities as they choose, including how they moderate user content. However, platforms must tell the user, the oversight body, and the public what their policies are (including the core values on which their policies are based) and how their policies are enforced, as well as how and when they use artificial intelligence, including machine learning tools.

- Establish an accountability regime to hold platforms to their promises: Given the concerns about illegal and harmful content online, a regulator should supervise the implementation of the transparency framework. This regulator should be empowered to set baseline transparency standards, require efficient and effective user redress mechanisms, audit compliance, and sanction repeated failures. The regulator should have insight into the moderation algorithms as well as the recommendation and prioritization algorithms, as discussed more fully below. Any accountability regime must be mindful of the unintended consequences of a one-size-fits-all approach. While the rules should apply equally, the regulator can use its discretion in enforcement to account for how rules might affect small- and medium-sized companies, ensuring that they do not become an insuperable barrier to entry nor prohibitive to operations.

- Create a three-tier disclosure structure: While respecting privacy, this structure would offer three tiers of information access, providing (a) users with platform rules and complaint procedures; (b) researchers and regulators with access to databases on moderation activity, algorithm decision outcomes, and other information; and (c), under limited circumstances such as an investigation, access to the most restricted classes of commercially sensitive data to regulators and personally sensitive data to researchers approved by regulators.

- Provide efficient and effective redress mechanisms: Transparency regulation alone does not provide adequate redress for users whose content has been removed or downgraded. Two complementary mechanisms can reimagine the design of public and private adjudication regimes for speech claims—social media councils and e-courts—and this report encourages further development of these tools on a local, national, or multinational basis.

- Social media councils: These independent external oversight bodies make consequential policy recommendations or discuss baseline content moderation standards, among other functions. A wide variety of structures is imaginable, with jurisdiction, format, membership, standards, and scope of work to be determined.

- E-courts: In a democracy, moderation decisions that implicate law or human rights require judicial redress. Given the potential volume of appeals, an e-court system has considerable appeal. It would have specially trained magistrates for swift online adjudication, and provide a body of decisions to guide future parties. Models include online small claims courts. Funding would likely come from public taxation or potentially a fee on online platforms.

- Use the ABC framework to combat viral deception (disinformation): In assessing the influence and impact through social media platforms, distinguish between Actors, Behavior, and Content (ABC). The biggest issue is generally active broad-based manipulation campaigns, often coordinated across platforms and promoted by foreign or domestic actors (or both) to sow division in our societies. These campaigns are problematic mainly because of their reach in combination with their speech. It can be more effective to address the virality of the deception that underlies these campaigns, such as the artificial means (online operational behavior) these actors deploy to promote their messages, before addressing the content itself. Crucially, states should use a wider range of tools to respond to foreign interference in democracies, including diplomacy, sanctions, and cyber-based actions.

“In less than a decade, online content moderation has gone from a niche issue to one of major global impact. Human rights standards should drive not only what companies do, but what governments and the public demand of them.”

Introduction and Background

Five years ago, regulating social media was a niche discussion in most democracies. Now, we are discussing how, not whether, to regulate online platforms.

Since 2016, lawmakers, journalists, civil society groups, and academics have criticized internet companies, and especially social media companies, for enabling the viral spread of disinformation, hate speech, subversion by hostile states, election interference, cyber-bullying, genocide, terrorism, extremism, polarization, revenge pornography, and a litany of other ills. The potential scope is vast—ranging from political speech to manifestly illegal content to content that may be harmful but is not illegal. Many believe that online hate speech and violent videos are connected to an uptick in extremist violence. Shootings and live-streamed terrorist attacks like that in 2019 in Christchurch, New Zealand, have accelerated pressure from governments to act. There are also widespread concerns that disinformation can undermine elections, whether by influencing votes or by undermining confidence in the results. The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced these concerns, as conspiracy theories swirl about false remedies for the virus, incite attacks on 5G telecommunications masts in Europe, and fuel anti-Asian racism.3

Governments need to act and make democracy more resilient. Many politicians in Europe and North America are frustrated, however, at what they see as the arrogance, commercially driven policies, and stalling tactics of the tech companies.4 Officials also worry that companies do not enforce their own policies or promises under self-regulatory regimes, and governments lack the ability to verify their claims. Meanwhile, the scope of harms is continually and rapidly evolving.

In response, governments are turning to legislation, introducing a raft of new regulations dealing with online content. To date, over 14 governments in Europe and North America have considered or introduced legislation to counter everything from “fake news” and “disinformation” to “hate speech.”5 Some laws, like Germany’s NetzDG, are already enacted, while other frameworks, like the UK legislation on online harms, are being debated.

Tech companies, many of which state that they are committed to freedom of expression, are increasingly taking ad hoc action, responding to pressure from government officials, the public, and their company employees alike. They argue that content moderation decisions are complex, the answers are not always clear-cut, and reasonable people may differ. Companies face many conflicting demands, among them, complying with privacy laws while being pressured to release data; moderating content at scale, while acting under time-limited takedown demands; interpreting a variety of conflicting national laws and enforcement; and potentially setting precedents by meeting demands in one nation that could be abused in another context. As a consequence, some companies have asked for regulation to help to clarify their responsibilities.6

Social media companies have coordinated and reacted significantly more swiftly to COVID-19 disinformation than with previous issues such as anti-vaccine campaigns.7 Their responses have included posting info boxes with links to trusted institutions, removing apps like Infowars for spreading COVID-19 disinformation, and even deleting misleading tweets from major political figures such as Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro.8 This illustrates a growing recognition by platforms of their moral/de facto responsibility as good corporate citizens for the content posted on their platforms.

Even as dynamics between governments and tech companies play out, many others, including some digital rights and civil society organizations, fear citizens’ speech rights may be undermined in the rush to address problems of online content. They argue that freedom of expression is a core democratic value and fundamental right, and that Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights9 makes no exception for hard-to-define categories like “disinformation” and “online harms.” They fear that governments may unintentionally undermine democratic values and international law by requiring platforms to police legal but harmful speech, which would go beyond illegal content such as child pornography. They warn that current suggestions may incentivize platforms to delete more content than necessary in order to avoid punitive government action. They also worry about privatized governance of speech by technology companies and are frustrated by the lack of transparency, by both governments and platforms.10

In short, governments, companies, and the public are all distrustful of one another. This mutual distrust inhibits them from working together to address the major online problems that occur as bad actors intensify their activities and more people spend more time online.

Along with challenges about how best to defend democratic values, there are differences in regulatory development across the transatlantic sphere. Government bodies in the UK, Germany, and the EU are rapidly developing regulation, while in the U.S., a mix of First Amendment traditions and partisan gridlock has stymied most attempts at federal legislation. European law, long rooted in traditions of the European Convention on Human Rights, typically accepts that expression may be subject to narrow restrictions in order to protect, among other things, the rights of minorities and public order. As a result, European governments may impose sanctions, for example, for occurrences of illegal hate speech and genocide denial, approaches that would be forbidden under American Constitutional constraints on speech regulation. These differences extend to attitudes toward online content.

Although Europe and North America have different approaches toward free speech, the similarities between them are much more significant, especially when compared with authoritarian regimes. Both Europe and North America see freedom of expression as a fundamental right that both promotes individual liberty and holds government to account. Non-democratic regimes, in contrast, are rapidly shaping their own versions of controlling expression online and their own ideas of sovereignty based on censorship and surveillance, and sharpening their methods of foreign interference.

The need to govern in line with democratic values when these are at stake online thus grows ever more urgent. If democracies cannot define a coherent, collective set of fundamental principles and governance frameworks, the field will be defined by political powers with very different ideals, or by private sector interests without accountability.

The Transatlantic Working Group was thus formed to find collective solutions that foster a positive and democratic online environment.

A transatlantic approach offers a first step to create international, democratically based solutions that can work in multiple countries. It seeks to counter further fragmentation where European and American regulations diverge dramatically. The proposals in this report aim to increase the responsibility of social media companies through greater accountability.

Democratic government initiatives must focus on creating a framework for transparency and accountability. Social media companies should be required to provide transparency about the policies they adopt to govern speech in their communities and their processes for enforcing those policies. Companies should be required to provide a process for effective redress of complaints about content moderation decisions. These requirements, however, should be enforced by an independent regulatory body that is empowered to monitor and audit company behavior and to authorize other trusted third parties to do so as well. This basic regulatory framework may be advised by social media councils and complemented by e-courts for expedient independent judicial review of alleged violations of free speech rights. Governments, then, should allow sufficient time to evaluate the effectiveness of these efforts before considering more expansive measures.

In this report, we discuss where selected current legislation may pose a challenge to freedom of expression and provide overall principles and recommendations derived from analyzing these initiatives. The report then offers an ABC framework for dealing with disinformation more comprehensively. Finally, we suggest three complementary solutions to build accountability: a transparency oversight body, social media councils, and e-courts. This report draws on the Transatlantic Group’s 14 research papers, which are available here.

“There is little in common between Russian trolls, commercial spambots, and my uncle sharing wrongful information on his Facebook page. Tackling disinformation effectively requires applying the right instruments to its sub-categories.”

Common Problems with Current Legislative Initiatives

Because the Transatlantic Working Group aimed to generate best practices that protect freedom of expression while appropriately dealing with hate speech, violent extremism, and disinformation, we began by comparing European and North American applications of that fundamental freedom, which enables citizens to hold each other, governments, and companies to account.11 There are obvious differences: while governments on both sides of the Atlantic have negative obligations not to suppress speech, European governments also have positive obligations to enable speech.

Yet in the exercise of freedom of expression, both sides of the Atlantic see common themes. The same major digital platforms operate on both continents. Both sides see the same imbalance between platforms, governments, and civil society; the same lack of trust; the growing desire of politicians from across the political spectrum to enact legislation and revisit intermediary liability; and the warnings by rights advocates that regulatory proposals should not erode freedom of expression. Although we mostly examined U.S.-based companies, the rapid rise of the Chinese video-sharing platform TikTok in the United States has shown, for example, that non-U.S. companies can quickly generate global reach. Any discussions about regulation cannot assume that digital platforms will be based in countries with similar ideals about freedom of expression.

The TWG analyzed a selection of laws, proposals, and private initiatives on three types of expression: hate speech, terrorist content, and disinformation.12 The papers then recommended best practices to improve those instruments. We did not evaluate antitrust/competition law or data privacy proposals as they were beyond our remit.13 We did, however, discuss the impact of new rules on smaller companies, which face disproportionately higher compliance costs relative to their revenues. We also considered nonprofit organizations like Wikimedia and the Internet Archive.

Five common patterns emerged in the initiatives we reviewed:

1. They focus on suppressing content without clearly defining what types of content are targeted.

Several instruments create new categories of regulated speech such as “disinformation” or “legal but harmful content.” Such generally described categories may be too broad to enforce reliably, create legal uncertainty, and risk chilling speech. Many initiatives do not differentiate between illegal content versus malign but legal speech. The UK Online Harms White Paper in 2019, for example, proposed the same overarching regulatory framework for everything from illegal content such as child pornography to the more amorphous “cyber-bullying.”14 The UK government’s response in February 2020 to initial feedback has now moved to “establish differentiated expectations on companies for illegal content and activity, versus conduct that is not illegal, but has the potential to cause harm.”15

2. They outsource further responsibility to platforms and undermine due process safeguards by deputizing platforms to undertake law enforcement functions.

Some governments and law enforcement agencies informally ask or pressure platforms to remove illegal content under their private terms of service, rather than proceeding under applicable law. The EU’s draft Terrorist Content Regulation encourages that process.16 Platforms are ill-equipped to make such judgments and may remove content rather than risk fines or more regulation. Such “outsourcing” of speech regulation is not transparent and creates new challenges for accountability and oversight. When governments restrict online speech, these measures should comply with due process principles and be subject to safeguards like judicial review. Informal agreements with private platforms obscure the role of authorities and deprive those unjustly affected of civil redress.

3. They foster further reliance on automated and AI-driven content moderation.

To moderate content rapidly at scale, platforms increasingly rely on AI and machine learning tools, coupled with human reviewers.17 Automation is capable of identifying spam, or comparing content against known files of copyrighted content or child sexual abuse imagery. But automation can be unreliable for “terrorist speech” or “hate speech,” which require nuanced, contextual assessment. Using AI to moderate these categories of content can lead to errors and potential over-deletion of legal content. Automated removal systems are imprecise and may also include systemic biases. Training data for AI tools may contain hidden inequalities, which are then amplified throughout the system. Automated moderation without adequate human oversight thus disproportionately threatens minorities or has other unintended consequences.18 Additionally, smaller platforms often cannot afford sophisticated content moderation systems. COVID-19 has confronted ever more intermediaries: shopping platforms now have to deal with fake cures and price gouging, while internet registries face a flood of website registrations related to the virus.

4. They insufficiently promote transparency and accountability.

Both NetzDG and the draft EU Terrorist Content Regulation include transparency reporting rules—a major step forward. But there is still a lack of independent oversight, as qualified researchers cannot review private sector data in greater detail to understand issues such as decisions on borderline content.19 Self-regulatory efforts to provide data access, like Facebook’s Social Science One program, have seen many bumps in the road. And some platforms have restricted access to public APIs and scraping tools. The EU Code of Practice on Disinformation contains several commitments on research access, including public archives for political advertising, but implementation to date has been inconsistent.20

The Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT) is a private-sector consortium of companies that have cooperated to create a database for automated content removal and downranking of images and videos. The database is not open to public oversight. It is unclear what content is treated as terrorist material, in part because much flagged content is deleted before anyone sees it.21

There is also a lack of transparency around algorithms and around government-requested takedowns, two further important areas.22

5. They conflate traditional media with the online world.

The dynamics of the online world differ radically from broadcast and print media. It is important to remember that disinformation or problematic content continues to be generated or amplified by broadcast or print media as well as online.23 Meanwhile, online platforms facilitate virality, and organize, prioritize, and distribute massive amounts of third-party and user-generated content from around the globe rather than only producing their own. Social media companies provide services to consumers in exchange for their personal data, relying on advertising revenues generated in part from microtargeting products and services to individuals. Nonetheless, policy makers have sought to extend much of existing media regulation to the online world. Instead, policy makers should focus regulatory attention on how content is distributed and manipulated through algorithms, and promoted, targeted, and amplified through ever-evolving mechanisms unique to the internet. Finally, much more research is needed on how online content travels and affects behavior online and offline. Some empirical studies generate counterintuitive results.24

These findings laid the groundwork to create recommendations on how to improve regulation in ways that are compatible with democratic principles, general European and North American regulatory environments, and free speech attitudes.

| Offline Media | Online Expression |

|---|---|

| Centralized | Distributed |

| Editorial Control | Ex post moderation User uploaded content Amplified by moderation, prioritization, and referral algorithms |

| High incremental distribution cost | Low incremental distribution cost |

| Geographic limitations | Global reach |

| Volume, reach, & speed constraints | Potential high volume, far reach, & speed |

The TWG Basic Principles

Whether making recommendations for regulation or for platform policies, our discussions focused on creating solutions that incorporated freedom of speech and human rights protections by design. Our discussions led to the following basic principles:

Clearly define the problem using an evidence-based approach: Policy measures directed at vaguely defined concepts such as “extremism” or “misinformation” will capture a wide range of expression. Before taking any steps to restrict speech, regulators should explain clearly and specifically the harms they intend to address, and also why regulation is necessary for this purpose. The rationale should be supported by concrete evidence, not just theoretical or speculative concerns. For that to be possible they need to know more about how information flows through private platforms. The transparency and accountability recommendations below would provide needed access to facilitate that understanding.

Distinguish clearly between illegal speech and “legal but harmful” content: If a deliberative democratic process has defined certain speech as illegal, that speech presents a different set of issues. But the parameters of illegality should be clearly defined to avoid chilling lawful speech. What speech is illegal varies within Europe and North America.

Remember that beyond social media platforms, the responsibilities for different-sized companies and for companies at different layers of the internet “stack” may vary: Expression online occurs through myriad channels, including email, messaging services, shared documents, online collaboration, intra-company and -industry channels and chat rooms, research communities, gaming and rating platforms, crowd-sourced wikis, comments on traditional media sites, and community platforms (including those run by governments), as well as the most-discussed global social media and search companies. The different players on the internet work in different sectors, provide different products and services, and have different business models, whether based on advertising, subscription, donation, public support, or other forms of income. These distinctions, as well as the differential impact of measures targeting different levels of the stack, require careful deliberation and nuanced approaches to regulation, as not all players have the same impact or the same technical and financial capabilities.

Carefully consider the role of intermediaries online and potential unintended consequences of changing intermediary liability. “Intermediary liability safe harbors” underpin the current online ecosystem, enabling platforms to host user-generated content without fear of being held liable.25 They are required, though, to delete illegal content when notified of it, while the generator of the content is liable for it.26 To promote both free expression and responsible corporate behavior, any intermediary liability safe harbor provisions should include both a sword and a shield, enabling platforms to take down problematic content under their terms of service (the sword) without incurring legal liability for that editorial engagement (the shield).27

Create and execute a vision for a productive relationship based on democratic principles between governments, the tech sector, and the public that includes:

- Greater transparency from tech companies, as detailed below.

- Greater transparency from governments regarding their interventions in content moderation.

- A simple and swift redress regime for users who wish to challenge content that they believe should be deleted, demonetized, or demoted—or content that remains online even after a request for removal is filed.

- Due process through judicial review of cases involving rights violations, e.g., by specialized e-courts rather than internal adjudication by platforms, as described below. When governments direct platforms to restrict online speech, their measures should comply with rule of law principles so that these measures are subject to judicial review. While companies continue to act on the basis of codes of practice, governments should not use informal agreements with private platforms to obscure the role of the state and deprive their target of civil redress.

- Effective enforcement mechanisms so that proposed solutions can be implemented and their efficacy measured. For governments this could include strengthening consumer protection rules to ensure that platforms engage in appropriate behavior toward their users and other companies.

- Regular evaluation of rules to ensure that they remain fit for purpose and are a proportionate response, especially when speech is involved. Sunset provisions are an excellent way to trigger reviews.

The ABC Framework: A Paradigm for Addressing Online Content

Fighting illegal and harmful content should focus on the distribution of content rather than the content itself—“reach” may matter more than speech.28 That reach may be very small (specific microtargeting) or very large (through artificial amplification). Both can have deep impact.

While illegal content presents specific challenges that are covered by laws, a focus on reach is particularly relevant when dealing with “viral deception,” or “the deliberate, knowing spread of inaccurate content online.”29 The origins of virally deceptive content may be domestic or foreign, private actors or governments, or a combination. The content itself may not be illegal or even false, but often is designed to sow distrust and divisions within a democracy.

The report builds on prior research to distinguish between bad Actors, inauthentic and deceptive network Behavior, and Content.30

- Bad actors are those who engage knowingly and with clear intent in disinformation campaigns. Their campaigns can often be covert, designed to obfuscate the identity and intent of the actor orchestrating them. These can be well-resourced and state-sponsored or they can be run by small groups motivated by financial gains. The methods of these “advanced persistent manipulators” change and their aims evolve over time.31

- Deceptive network behavior encompasses myriad techniques to enable a small group to appear far larger than it is and achieve greater impact. Techniques range from automated tools (e.g., bot armies) to cross-platform coordinated behavior to manual trickery (e.g., paid engagement, troll farms).

- Focusing on content can lead to a “whack-a-mole” approach. Most importantly, it fails to understand that information operation campaigns, such as the infamous Russian Internet Research Agency (I.R.A) campaign in the U.S., often use factual but inflammatory content in their activity to sow dissension in society. Content can still matter, for example in public health, but problems are exacerbated when content is combined with bad actors and network behavior.

Focusing on bad actors and deceptive network behavior may eliminate more harmful content—and have less impact on free expression—than attacking individual pieces of content. This does not imply eliminating anonymity or pseudonymity online is a way to address malign actors engaging in disinformation campaigns. These tools protect vulnerable voices and enable them to participate in critical conversations. Whether to allow anonymity should be a matter of platform choice, and stated in their terms of service. Malicious actors often prefer impersonation or misrepresentation. Banning anonymity and pseudonymity risks preventing participation from vulnerable voices while doing little to eliminate campaigns from hostile states, intelligence services, and other manipulative actors.

In information operations, where state actors are involved either directly or indirectly in viral deception, the remedy lies less in speech legislation than in governments deploying other tools such as attribution, diplomacy, economic sanctions, or cyber responses. Transparency and cooperation between government and platforms are essential in these cases to enable officials and others to access data, conduct cross-platform investigations, and draw their own conclusions.32 Enacting and enforcing restrictions on foreign governments’ financial or in-kind contributions to political campaigns is also essential. Authoritarian nations should be criticized if they use democratic government actions to justify anti-democratic measures to block or repress legitimate voices.33

Major online companies have greatly improved their ability to identify false accounts and attack unauthorized attempts to artificially promote certain content34 and users, without reference to the underlying content. Greater cross-company coordination to ensure timely exchange of data on inauthentic accounts or techniques used by malicious actors should be encouraged in a transparent way.

The question of “inauthentic” behavior is particularly troublesome with respect to political advertising. The EU Code of Practice on Disinformation requires political ad transparency, while in the U.S. the Honest Ads Act (HAA) would similarly require a publicly available archive of political advertisements, which major social media companies are now working on (even if the archives are incomplete).35 The HAA also requires immediate disclosure to the ad recipient of who is paying for the ad and would apply existing regulation for TV and radio ads to online ads.36 The Election Modernization Act passed in Canada in 2019 similarly requires an ad archive during elections.37

Microtargeting of voters has been identified as a key disinformation tool. Many parliamentary committees have recommended that it should be limited.38 One option is to limit microtargeting categories to larger ones, such as age or ZIP code, although caution is warranted to avoid disadvantaging lesser-known candidates or organizations with fewer resources.39 Another option would require real-time disclosures about ads, such as the size of the targeted audience, criteria for selecting recipients, and the payment source.40 Data collection and retention policies are crucial to limit manipulation and harmful reach online.

Focusing on regulating deceptive actors and behavior does not remove responsibility from companies to improve how they deal with content. The current pandemic highlights the urgency. Online platforms have taken different approaches to COVID-19 mis- and disinformation, and many have proactively coordinated with government officials and other platforms to refer users to official data from the World Health Organization and national authorities, and remove misleading advertisements and price-gouging ads. While YouTube bases its removal policies solely on the content of videos, Facebook and Twitter make exceptions in doing so for some individuals, such as prominent politicians.41 A publicly available post-pandemic assessment of platform policies and their effectiveness should provide valuable best practices and lessons learned.

Tech companies should also provide greater clarity on how they police disinformation.42 While a few available tools enable open-source investigations, platforms know far more than governments or external researchers. Even within platforms, more empirical research can help their leadership to improve their own tools and better combat disinformation.43 The broader impact of platforms and their business models on the spread of disinformation has not been sufficiently assessed, either. Some platforms’ community standards or terms of service either indirectly prevent external research or directly block it. Regulatory oversight and access to information for academic research are both needed to offer insights.

The lack of transparency by digital platforms undermines trust in platforms themselves. In the absence of information, governments and civil society often fear and assume the worst. Platforms may worry that opening up to researchers could lead to another Cambridge Analytica-type scandal, in which data ostensibly used for research is weaponized for elections and profit. An oversight body to set ground rules for research and to provide legal guidance on what they can reveal to whom, where, and when would reduce that risk.

Transparency and Accountability: A Framework for a Democratic Internet

A key step to build accountability is a mandatory transparency regime, overseen and enforced by a supervisory body, assisted by vetted third-party researchers and others. That conclusion reflects the importance of freedom of expression to democratic societies, the advantages and harms of existing and proposed measures to address online speech, and the distinctions between actors, network behavior, and content.

While transparency is not an end in itself, it is a prerequisite for creating a new relationship of trust among tech companies, the public, and government. There is much we do not know about platforms and there is much that platforms themselves do not have the capacity or will to investigate, such as the downstream effects of the dissemination of certain messages, based in part on the operation of particular algorithms.44 There is also an overabundance of studies about particular platforms, especially Facebook and Twitter (the latter has a more open API than other major platforms, even if it has fewer users). This can lead to a skewed understanding of the online environment.

Transparency can achieve many aims simultaneously: enable governments to develop evidence-based policies and strengthen their ability to exercise independent oversight; push firms to examine issues or collect data that they otherwise would not; empower citizens to understand their information environment. To be effective, however, transparency must be accompanied by enforcement and accountability.

Democracies can promote and mandate transparency in myriad ways. Working in tandem across the Atlantic on complementary transparency rules would eliminate conflicting requirements and enhance research capabilities. Encouragingly, draft rules in some jurisdictions are moving toward a transparency and accountability-based approach, perhaps in response to public consultation, as in the UK.45

Mandating and Enforcing Transparency

Discussions about transparency should focus on internet companies that host user-generated content for broader public dissemination—generally, social media companies but not limited to them. These recommendations may apply as well to messaging services, search engines, and others, although they may need to be adjusted depending on the specific service. Alternative definitions for companies subject to such rules are set forth in the UK Online Harms Paper, NetzDG, and U.S. Sen. Mark Warner’s (D-VA) proposed pro-competition legislation.46 To avoid unintended consequences, the scope of affected companies should be defined tightly at first in order to create manageable legislation and expanded later based on experience.

As a starting point, all such companies can and should be required to establish clear terms of service and community standards about allowable speech on their platforms (including, of course, a prohibition on speech deemed illegal in the jurisdiction). Such standards can and will vary among the sites, for communities differ, as do the sizes of companies. But clear and easily accessible standards make it easier to apply existing consumer protection laws if a platform is not abiding by its own terms of service. There also needs to be clear guidance on any sanctions for noncompliance.

Transparency should include data on how platforms enforce their terms of service to enable assessments by the public, researchers, and governments. Those data should include information on takedowns as well as instances when content remained on the site after the company had been notified of a potential violation of terms of service or law. Platforms should be required to establish a process to notify users if their content is removed or downgraded, and to have an effective process of redress should users object to moderation decisions. In particular, companies should promptly explain to those whose content was deleted, demoted, or demonetized what specific rule was violated and why that conclusion was reached; inform users if the decision was automated; and explain redress procedures if a complaint is rejected or inappropriate.

Transparency requirements for digital platforms also should include the core structure of the algorithms and how they were developed or trained. These disclosures would apply to the underlying recommendation and prioritization algorithms as well as moderation algorithms.48 This would not require companies to reveal their “secret sauce,” but must be sufficient to enable auditors and vetted researchers to investigate potential discrimination, microtargeting, and unintended impacts of algorithmic processing.49

These transparency mandates should be overseen by independent bodies, ideally government, but different jurisdictions may adopt other approaches to create or empower a transparency oversight body, regulator, or external auditor to set and enforce transparency rules, investigate complaints, and sanction offenders. Three approaches to transparency oversight bodies include the use of (1) a new or existing regulatory agency (e.g., the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the French Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel (CSA), the British OFCOM, or the European Commission for Values and Transparency) (2) an industry association similar to the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) or (3) independent social media councils, potentially in conjunction with governments, civil society organizations, technical groups, and academics. In the last case, enforcement likely would be limited to public criticism of failure to live up to agreed-upon standards. (The Christchurch call is an example of this approach.)

- Transparency is fundamental to democracy. When running political ads, platforms should verify the existence and location of the advertiser, and provide information on source of payment, size of targeted audience, and selection criteria for targeting recipients (while protecting privacy).

- Rules should set limits on political microtargeting, such as minimum size of group or restrict permitted categories, mindful that nascent campaigns with fewer resources need smaller reach.

- Regulation should require platforms to maintain a robust political ad database for independent researchers.

Within the context of the governing law, the supervisory body should be empowered to set minimum transparency requirements, audit compliance, and issue sanctions. While the basic rules governing transparency should apply to all affected platforms, the supervisory body can and should have discretion in enforcement, and should focus primarily on those firms with significant reach—such as the numbers of users within a jurisdiction, relative to the size and scale of the market. For smaller companies, there could be a sliding scale or they could be included at a later time. While much pernicious activity occurs on smaller sites, an initial focus on larger platforms and those with the most impact on public discourse might enable legislation to develop iteratively.

A tiered system of transparency should be created, with different levels of information directed to the public, researchers, and government.50 Such systems already exist for other types of sensitive data like health or taxes.

- Users should be able to easily access platform rules and complaints procedures. There should be clear and simple instructions on appeals processes and the range of enforcement techniques.

- Regulators and vetted researchers should have access to more data, including political ad disclosures; data on prioritization, personalization, and recommendation algorithms (not the source code but the goals behind them and key factors); anonymized data for conducting content moderation audits; and complaints.

- Access to the most restricted class of data should be provided, if at all: (a) in the case of commercially sensitive data, only to regulators conducting an investigation; or (b) in the case of personally sensitive data, only to researchers approved by regulators.

The system outlined above assumes that laws governing transparency and its oversight will be applicable in specific jurisdictions, generally at a national level or on the level of the European Union (27 national jurisdictions). The focus on transparency will help to minimize conflict of law issues, including those that may arise in the transatlantic space, where larger global platforms operate. In the EU context, there are already multiple examples in which the lead enforcement authority is based where the company is headquartered, with strong mechanisms to promote cooperation with authorities in the other countries where a company operates.

Transparency can be a powerful force for change in multiple ways. Sometimes, public outcry changes platform behavior or prompts people to choose an alternative. Journalistic investigations have, for example, sparked regulatory investigations: ProPublica’s work provided evidence for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to sue Facebook for its housing advertisements practices in March 2019.51 In other cases, regulatory investigations may lead to suggestions for legislation, but under a transparency regime, proposals for new laws would be based upon evidence of how the companies actually work. In the meantime, platforms should adopt more robust transparency measures rather than wait for legislation to be enacted.

In addition, law enforcement and other government agencies should be required, with certain exceptions, to provide data on the volume and nature of requests to platforms to take down content.

“Transparency requirements are more potent and effective than content-based liability. Platform transparency will help citizens understand what it means to live in algorithmically driven societies.”

Redress and Standards Setting Mechanisms

Transparency regulation alone does not solve the need for adequate redress for users whose content has been removed. Nor does it offer more collaborative approaches to policy-setting for social media firms, some of which play an outsized role in the public square. Social media councils and e-courts are two additional complementary mechanisms with which we can reimagine the design and adoption of public and private standards, as well as redress regimes for deletion, demonetization, or deceleration of speech, or failure to remove content that violates law or terms of service.52

Social media councils

Social media councils offer independent, external oversight from public, peer, or multistakeholder sources. A high-level, strictly independent body to make consequential policy recommendations or to review selected appeals from moderation decisions could improve the level of trust between platforms, governments, and the public. Policy makers and multistakeholder groups might consider a wide range of organizational structures and precedents to choose from, with format, purpose, jurisdiction, makeup, member selection, standards, scope of work, and scalability to be determined in line with the underlying mission of the council.

While social media councils are a relatively new concept, existing models of private self-regulatory organizations (SROs) provide insight into possibilities. An example of a multistakeholder organization is the Global Network Initiative, a non-governmental organization with the dual goals of preventing internet censorship by authoritarian governments and protecting the internet privacy rights of individuals. It is sponsored by a coalition of multinational corporations, nonprofit organizations, and universities.53 An example of an industry-created organization is the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), a private, independent regulator of securities firms that sets ethics standards and licenses brokers in the United States. With oversight by the Securities and Exchange Commission, it fosters a regulatory environment that promotes collaboration, innovation, and fairness. Its board members are chosen by the industry.

A multistakeholder council or an industry-created council could enable greater collaboration and information-sharing by companies, facilitating early detection of new behaviors by bad actors across multiple platforms; provide a ready-made forum to discuss responses in crisis situations such as the Christchurch massacre, or advanced crisis planning; set codes of conduct or establish baseline standards for content moderation that safeguard freedom of expression; set standards and procedures for independent, vetted researchers to access databases; and make companies more accountable for their actions under their terms of service.

As advisory bodies, councils can provide guidance and a forum for public input, for example in cases where content that spreads hateful, extremist, or harmful disinformation, such as fake COVID-19 cures, is allowed to remain up. They also might be empaneled as an appellate or case review board to select and decide appeals from company decisions in problematic cases of content moderation.

Notable debates on the purpose and structure of social media councils have envisioned two divergent paths: (1) a global council, advocated by the Stanford Global Digital Policy Incubator, to develop core guidelines grounded in human rights principles for how to approach content moderation online; evaluate emblematic cases to advise platforms; and recommend best practices for platforms regarding their terms of service; and (2) a national or regional council structure, advocated by ARTICLE 19, to give general guidance to platforms and resolve individual appeals predicated on human rights claims.54

The geographical scope may be national, regional, or global, or possibly a global body linking national or regional groups.

By bringing together stakeholders and multiple companies, social media councils offer a fundamentally different approach from single-company efforts, such as Facebook’s newly created Oversight Board, which is tasked with providing outside direction around content.55 Because Facebook has selected the members of the Oversight Board, its structure does not meet the standard of independence generally envisioned for social media councils. While the Facebook Oversight Board may improve Facebook’s moderation decisions, it is not a substitute for independent social media councils. Research should be conducted after a reasonable period of operation to distill the lessons learned from this effort.

E-courts

Any decision to censor the expression of a citizen is of immense consequence for democratic societies. This is why decisions determining some content to be illegal are weighty and should be thoroughly debated. In any democracy, a decision by the government to silence speech can be acceptable only after appropriate independent judicial review, whether that decision affects content online or offline. A system of e-courts would enable users to resolve disputes over content deletion through public scrutiny when the fundamental right of freedom of expression is involved. It would also enhance legitimacy through due process and independence, and protect democracy by bringing decisions about the legality of content into public view.

Nations or their judiciaries should consider establishing e-courts specifically for content moderation decisions when the legality of the speech or the potential denial of fundamental rights are at issue. Courts today generally are not well-equipped to handle at scale and in a timely fashion a massive number of cases involving appeals from platform content removal decisions that involve free speech, hate speech, or incitement to violence. The e-court concept potentially would provide that relief: a swift, simple and inexpensive, fully online procedure (no physical presence of parties) to resolve appeals of tech company decisions, with specially trained judges (magistrates) presiding. As envisioned by one jurist, such an internet court would have an abbreviated procedure, similar to that of a small claims court, with no right of appeal to general courts. Regular publication of case law compilations would offer guidance for future cases. Funding for e-courts could come through public taxation or a special tax on online platforms.

The e-court concept should be tested in a country and evaluated for its effectiveness and scalability. Many court procedures are now moving online during the COVID-19 crisis, suggesting that online adjudication might become more prominent, feasible, and accepted.

“Twitter is not The New York Times. It is Times Square. The public conversation you hear there is like the one you hear online.”

“Hate speech is free speech, too, but if it is allowed to reign, speech will no longer be free.”

Conclusions

Global freedom declined in 2019 for the fourteenth year in a row in what Freedom House has called “a leaderless struggle for democracy.”56 Citizens and officials in democracies worry about how social media platforms are contributing to the decline of democracy. As the COVID-19 crisis increases reliance on virtual connections, it is more urgent than ever to ensure that democratic values underpin our approaches and policies in the online world.

It is impossible to eliminate all illegal or harmful content online. But effective democratic tools can reduce the impact and spread of that content substantially. Democratic governments have a unique opportunity to build a legitimate framework for platform governance based on democratic values—principally freedom of expression and human rights, along with the rule of law. In our analysis, we have examined the distinct and complementary roles played by governments, platforms, and civil society in coming together to achieve this important goal.

Our report offers forward-looking proposals that aim to increase the overall responsibility of technology companies through enhanced accountability. Trust, transparency, and accountability can provide sound working principles. Greater transparency can increase trust between companies, governments, and the public, coupled with accountability to ensure oversight and compliance. Those principles can be implemented on both sides of the Atlantic through three complementary vehicles: a transparency regime, social media councils, and e-courts. Indeed, the development of transparency rules, accountability regimes, and supervised data repositories for vetted researchers are compelling areas for greater transatlantic cooperation.

In a series of frank, intense, but always constructive multiday discussions in the United Kingdom, United States, and Italy, the Transatlantic Working Group took an intellectual journey: from philosophical and cultural divisions between members to identifying common principles and concrete solutions. We did not deal with all issues in this space. Nor did our views always align. However, the democratic frameworks and mechanisms presented in this final report recognize and address the negative effects of online activity without undermining freedom of expression. These solutions can help to build a world where global freedom can increase once more.

“At a fraught time when much of the globe is locked down and interacting virtually, conspiracy theories, hate speech, and disinformation are flourishing, undermining democratic values and responsible health behavior. So this report—with recommendations that promote truth and civility online—could not be more timely.”

Partners and Sponsors

The Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania was founded in 1993. By conducting and releasing research, staging conferences, and hosting policy discussions, its scholars have addressed the role of communication in politics, science, adolescent behavior, child development, health care, civics, and mental health, among other important arenas. The center’s researchers have drafted materials that helped policy makers, journalists, scholars, constituent groups and the general public better understand the role that media play in their lives and the life of the nation.

The Institute for Information Law (IViR) is the lead European partner for the project. Established in 1989, it is one of the largest research centers in the field of information law in the world. The Institute employs over 25 researchers who are active in a spectrum of information society related legal areas, including intellectual property law, patents, telecommunications and broadcasting regulation, media law, internet regulation, advertising law, domain names, freedom of expression, privacy, digital consumer issues and commercial speech. The Institute engages in cutting-edge research into fundamental and topical aspects of information law, and provides a forum for debate about the social, cultural and political aspects of regulating information markets. The Institute for Information Law is affiliated with the Faculty of Law of the University of Amsterdam.

The Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands operates The Annenberg Retreat at Sunnylands, which hosts meetings in Rancho Mirage, California, and other locations for leaders to address serious issues facing the nation and the world. Sunnylands was the site of the historic 2013 summit between U.S. President Barack Obama and President Xi Jinping of the People’s Republic of China and the 2016 US-ASEAN Leaders summit. The Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands is a private 501(c)(3) nonprofit operating foundation established by the late Ambassadors Walter and Leonore Annenberg.

The Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands approved a grant in support of the TWG as part of the Dutch government’s commitment to advancing freedom of expression, a fundamental human right that is essential to democracy.

Acknowledgments

Experts and Advisors

We thank these individuals who have generously contributed their expertise: Madeleine de Cock Buning, Evelyn Douek, William Echikson, David Edelman, Ronan Fahy, Timothy Garton Ash, Doug Guilbeault, Nathaniel Gleicher, Ellen Goodman, Jaron Harambam, Sasha Havlicek, Brewster Kahle, Daphne Keller, Jeffrey Kosseff, Nicklas Lundblad, Frane Mareovic, Nuala O’Connor, Yoel Roth, Bret Schafer, Michael Skwarek, Damian Tambini, Alex Walden, Clint Watts, Richard Whitt, and Clement Wolf.

We are deeply grateful to Judge Róbert Spanó for his astute insights.

Sponsors and Partners

Annenberg Public Policy Center: Lena Buford, Daniel Corkery, Monica Czuczman, Samantha Fox, Ellen Iwamoto, Emily Maroni, Zachary Reese, Karen Riley, Michael Rozansky

The Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands: David Lane

The Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the United States: Martijn Nuijten

Institute for Information Law, University of Amsterdam (IViR): Rosanne M. van der Waal

German Marshall Fund of the United States: Karen Donfried, Karen Kornbluh

Ditchley Park Foundation: Tracey Wallbank

Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center: Bethany Martin-Breen, Pilar Palaciá, Nadia Gilardoni

MillerCox Design: Neal Cox, Jennifer Kaczor